Austria and Vicinity

Vienna is the capital and largest city of Austria. Austria (called Österreich

by its inhabitants) is not a large country from a population standpoint, with fewer than

9 million people living within its borders. Nearly two million of these people live in

Vienna, with 2.6 million in Vienna's metropolitan area. Vienna has the second-most

German-speaking inhabitants of any city in the world (after Berlin), and none of them

call their city "Vienna". Instead, the city goes by its German name, Wien

(veen). This name finds its way into some of the local food, including some of the

indigenous sausages (called wieners) and the famous wienerschnitzel (a

Viennese schnitzel; a schnitzel is a piece of meat, traditionally veal but usually pork

in practice, which is beaten into paper-thin submission, breaded and deep-fried). In

the U.S. there are canned things called Vienna sausages, but they don't come from

Vienna – they come from Armour or Libby (apparently Hormel doesn't make them anymore).

In any case, if you're in a German-speaking location and are looking for a train to

Vienna, you need to look for the name "Wien".

None of this helps if you're in Hungary, as we were. In Hungary, Vienna is known as

Bécs (don't ask – see the Budapest pages for

some background on Hungary's impenetrable language). Figuring this out reduced our

stress level immensely at the Budapest train station, where we began our two-hour ride

to Austria. Our trip was mostly uneventful, though the weather was taking a turn for

the worse. But the rain and the motion of the train had a hypnotic effect, and when we

weren't taking video of the passing countryside, we had time to reflect on some of the

history behind our destination.

Windmills from Train

The area of present-day Vienna, located on the Danube River (upstream from Budapest), has

been inhabited since at least 500 B.C. Evidence of Celtic settlers has been found, going

back to this period. The Romans thought enough of the site to establish a frontier city

here in 15 B.C. (called Vindobona), as an outpost to defend against Germanic tribes

(the Danube marking the border of the empire at the time). The emperor Marcus Aurelius

made the outpost famous at the time, dying here from disease in the year 180. Some of the outpost's

layout is reflected in the present-day Vienna street plan, and small areas of excavated

ruins can be seen by visitors in places. In the early Middle Ages, a count named Leopold

of Babenberg acquired control over a small district on the eastern border of Bavaria.

Leopold and his successors gradually increased the size of their territory eastward until

it became the Duchy of Austria. Around this time its expansion had grown to encompass the

city of Vienna, and the House of Babenberg moved their primary family residence here in

1145.

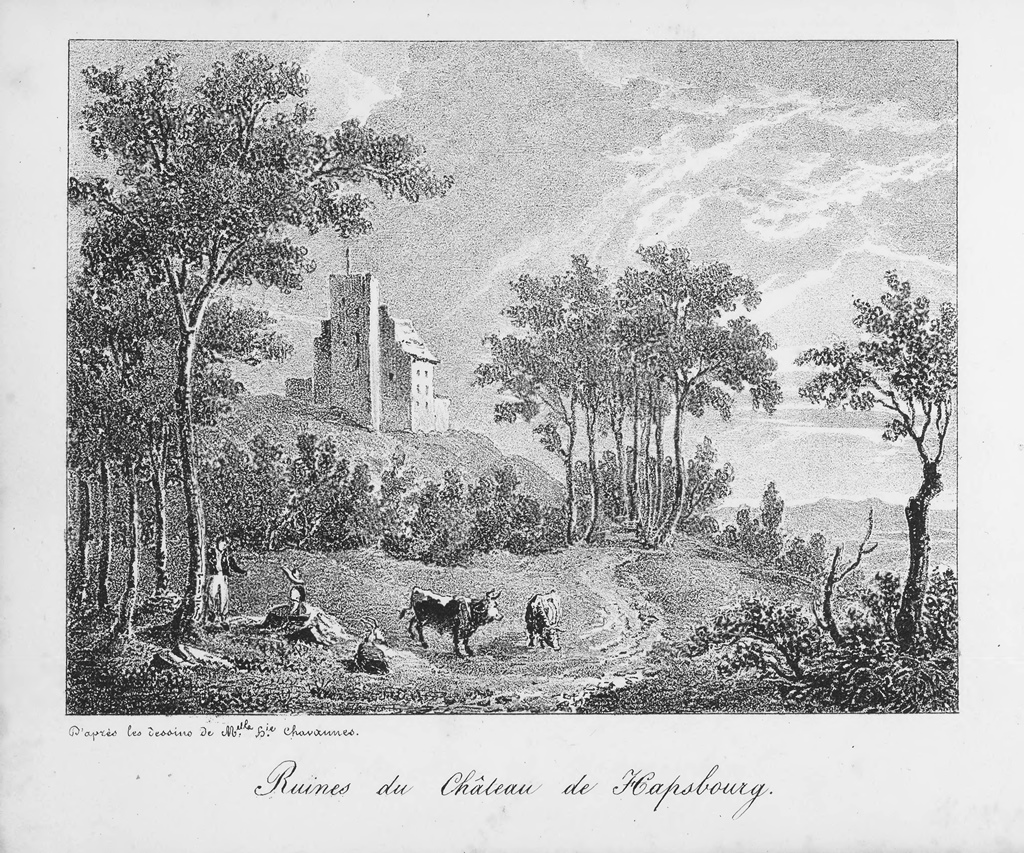

Meanwhile, over in Switzerland, another count, named Radbot of Klettgau, had built

himself a castle (in the present-day canton of Aargau), around the year 1020. He needed a

name for his castle, so he came up with "Habsburg" (sometimes spelled "Hapsburg"). Radbot

and his descendants proved to be social climbers, and they began to expand their territory,

through a combination of political maneuvering, arranged marriages, and the acquisition of

lands that became ownerless through the extinction of family lines. In 1108 Radbot's

descendants started to refer to their family by the name of their ancestral castle,

becoming the House of Habsburg. Eventually their wheeling and dealing made them a very

influential family, with connections extending to Swabia and Upper Alsace.

Habsburg Castle

Back with the Babenbergs, things weren't going so well. In fact, in 1246 their

leader, Frederick II (known as "the Quarrelsome"), managed to get himself killed while

fighting against the Hungarians, and since he did not have a male heir, this brought

the House of Babenberg to an end. This put the Babenberg holdings (including Austria)

up for grabs, and they were quickly grabbed by the king of Bohemia, Ottokar II.

Around this time another dynasty was also ending, the Hohenstaufen dynasty, from which

Germanic Kings of the Romans had been regularly elected. "King of the Romans" was a

position to which all other Germanic kings were subordinate, and was voted on when

necessary by several "prince-electors" scattered around the Germanic territories.

Kings of the Romans were often promoted to Holy Roman Emperor. After the

Hohenstaufens became extinct, there was a period of instability, but a proper election

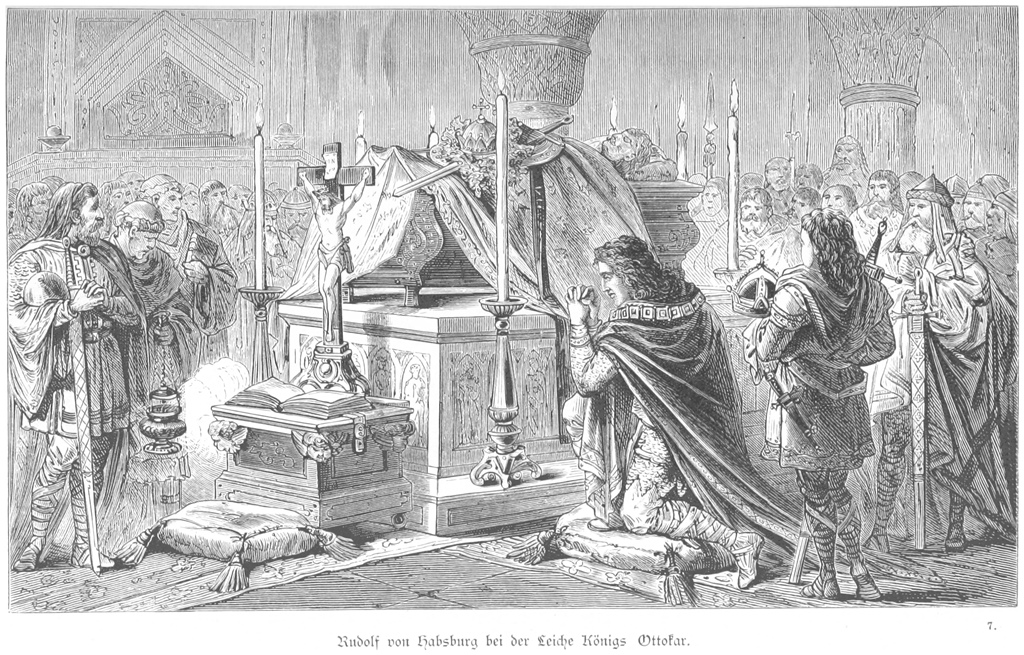

was eventually held in Frankfurt in 1273, and the winner, much to his surprise, was

Rudolf, head of the House of Habsburg (Ottokar II had been the prohibitive favorite,

but many of the electors had been uncomfortable with his rapid rise in power). So

Rudolf became Rudolf I, and Ottokar became royally pissed. This situation could only

be resolved on the battlefield, and after a few years of alliance-forming, it was, on

the plain east of Vienna, in 1278. Rudolf and his allies eked out a narrow victory,

but Ottokar did not survive the battle, ending any real challenges to Rudolf's election.

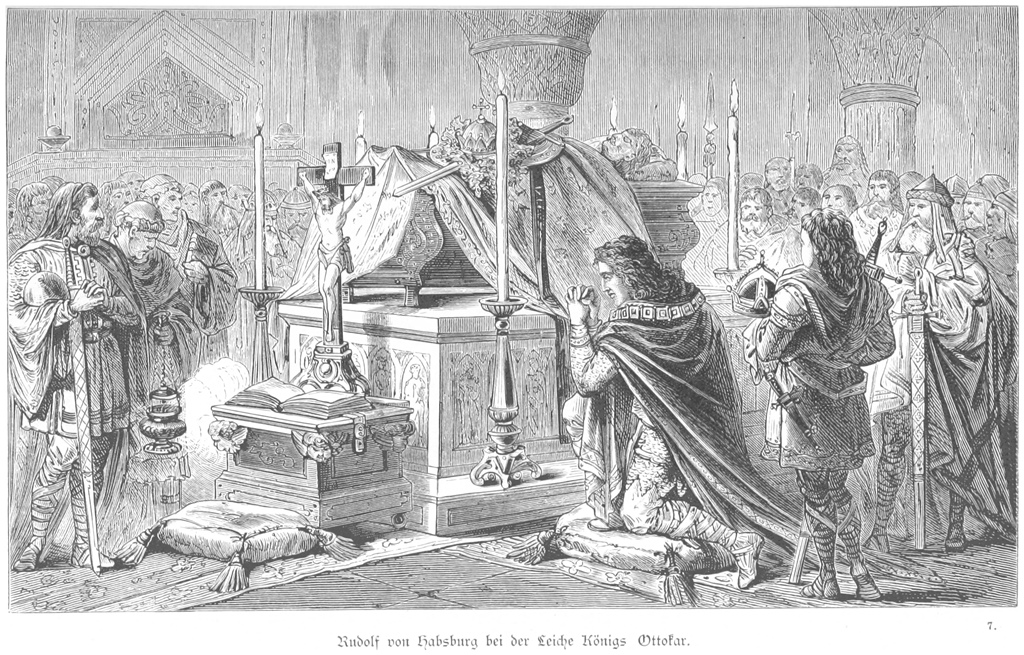

Rudolf I at Funeral of Ottokar II

Rudolf claimed the former Babenberg territories, beginning several centuries of

Habsburgs in Austria, and suggested that the Pope elevate him to Holy Roman Emperor.

The Pope, however, had other ideas (he must have been an Ottokar fan), and Rudolf

never did achieve the emperorship. And his son Albrecht I, though eventually

elected King of the Romans, never did either. After Albrecht there were many years

during which Habsburgs were not elected to anything, and their holdings dwindled

somewhat, but they remained dukes in Austria.

This changed in the middle of the 15th Century. By this time the Habsburg holdings

had become somewhat fragmented among different lines of Habsburgs, but one Habsburg,

Albrecht V, was able to break through and get himself elected King of the Romans in

1438. But this didn't last long, as he died in 1439. Other deaths in the family left

another Habsburg, Frederick V, in charge of pretty much everything. After

consolidating his power by not dying, Frederick was also elected King of the Romans,

in 1440. A decade later, Frederick, again having the good sense to remain alive,

was named Holy Roman Emperor, being crowned Frederick III in Rome by Pope Eugene IV

in 1452.

Emperor Frederick III

During his visit to Rome, he also took time to get married, to Princess Eleonora of

Portugal (who was crowned Empress). Frederick and Eleonora produced several children,

but only two survived to adulthood, the eldest of whom followed his father as

Maximilian I, again King of the Romans and Holy Roman Emperor.

Maximilian and his wife, Mary of Burgundy, also had only one surviving son, who

became known as Philip the Handsome. Those of you who read through

the Spain pages

might recognize this name as the Habsburg who married into the Spanish royal family

through marriage to Joanna ("the Mad"), daughter of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella.

You might also remember that Philip died before his father, but that his and Joanna's

son, Charles, eventually became both Holy Roman Emperor (as Charles V) and the first

true king of Spain (as Charles I; Ferdinand and Isabella were monarchs of Aragon and

Castille, respectively).

Emperor Charles V

The reign of Charles must have been exhausting – the Habsburg holdings were being

attacked by ongoing wars with France, a major offensive by the Ottoman Turks (led

by Suleiman the Magnificent; they were stopped at the 1529 Siege of Vienna) and a

surge of Reformation sentiment in the Germanic states. At the same time,

conquistadors were sending back riches from the New World, without which the ongoing

conflicts would have been difficult to afford. In 1555's Peace of Augsburg, Charles

was forced to concede the existence of Lutheranism in much of the Germanic territory,

and in the following year he abdicated at the tender age of 56. First, he yielded

the throne of Spain to his son, who became Philip II, and seven months later he gave

up the crown of the Holy Roman Empire in favor of his brother, who became Ferdinand I.

Ferdinand had already been ruling the Habsburg hereditary lands (including Austria)

in his brother's name, so this was not a major change for the Austrians.

The abdication of Charles V created a division (though an amicable one) in the

Habsburg dynasty between the Spanish Habsburgs and the Austrian Habsburgs. The

Spanish Habsburgs became extinct in 1700 with the death of Charles II, who named a

grandnephew of the House of Bourbon (the dynasty, not the saloon) as his successor,

starting a line of Bourbon Spanish kings. The Austrian branch technically became

extinct with the death of Empress Maria Theresa in 1780. Not that she didn't have

any children – she had 16, 10 of whom lived to adulthood (the youngest was

Marie-Antoinette, who was married off to the King of France). But dynastic lines

were only considered continuous if there is an unbroken line of male succession, a

line broken for the Habsburgs with the death of Maria Theresa's father, Charles VI.

Empress Maria Theresa

The royal succession continued (Maria and her husband, Francis I, produced two

future Holy Roman Emperors), but under the House of Lorraine name, of which her

husband was a member. But people were so used to the Habsburg name that the new

line of succession was (and still is) often called the House of Habsburg-Lorraine,

or sometimes just a branch of the House of Habsburg.

The Holy Roman Empire was dissolved in 1806, following a decisive defeat at the

hands of Napoleon in the Battle of Austerlitz. However, the emperor at the time,

Francis II (grandson of Maria Theresa and Francis I) had created a new Austrian

Empire consisting of Habsburg lands in 1804 with himself as monarch, as insurance

against the possibility of Napoleon getting himself named Holy Roman Emperor.

Napoléon at the Battle of Austerlitz, François Gérard

The new Austrian Empire (later Austria-Hungary) survived, with Francis and his

Habsburg-Lorraine successors as sovereigns, until 1919. But the 20th Century wasn't

kind to the Habsburg-Lorraines. The suicide in 1889 of Emperor Franz Joseph and

Empress Elisabeth's only son, and the death of Franz Joseph's younger brother Karl

Ludwig in 1896 left Karl Ludwig's son, Franz Ferdinand, as the heir to the Austrian

throne. But things changed catastrophically for the Habsburg-Lorraines and Austria

(and for the rest of the world) on a June day in 1914, when Franz Ferdinand and his

wife Sophie were assassinated in Sarajevo, triggering World War I.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand and wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg

Rendering of Assassination of Franz Ferdinand and Sophie

Alliances being what they were, Austria found itself fighting with Germany during this

war. When the war ended with Germany and Austria on the losing side, the consequences

for both countries were severe. I won't get into the consequences for Germany here,

but as for Austria, the victors were sympathetic to the desires of the empire's ethnic

minorities to leave the empire, and 60% of Austrian territory was lost, either to

existing countries (e.g. Italy and Romania) or to newly-formed ones (e.g.

Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia). Austria was also re-formed as a republic – the

Habsburg-Lorraine emperor (Charles I, also King Charles IV of Hungary, who had become

emperor in 1916 on the death of his uncle Franz Joseph) was suddenly out of a job, and

was ordered to leave the country, never to return. Charles made some unsuccessful

attempts to restore the monarchy, but ended up dying from pneumonia on the Portuguese

island of Madeira in 1922, at the age of 34. His brief faith-based rule and his

efforts to make peace during the war drew praise from Catholic leaders, and Charles

was eventually beatified by Pope John Paul II, in 2004. Thus ended the House of

Habsburg-Lorraine in Austria, but not its legacy. Vienna still has Habsburg written

all over it, as you will see.

Emperor Charles I

The republic thing didn't work out too well in Austria, and the Austrian government

didn't take long to evolve into a one-party state with a chancellor who ruled by

decree. Germany evolved in a similar way, with the Austrian-born Adolf Hitler

becoming chancellor. Germany became interested in uniting with Austria, largely at

the urging of Hermann Göring. The Austrian chancellor and many of the Austrian

people resisted the idea, but Hitler became insistent, and in 1938 sent German

troops across the border. To the surprise of many (including the Germans), the

troops were widely welcomed by cheering crowds waving Nazi flags, and Austria was

pretty much absorbed into Nazi Germany without incident, in an event known as the

Anschluss.

Hitler Speaking to Austrian Throngs

Persecution of Austrian Jews began immediately. Many were allowed to leave the

country, but only if they could pay a major tax, and only if they left all of their

belongings behind. Nearly all of the Jews who remained (about 65,000 of them) ended

up in concentration camps (mainly Dachau). The ensuing world war of course resulted

in the crushing defeat of the Nazis, and among many other places, horrific damage was

suffered by the Austrian capital of Vienna, at the hands of both Allied (mainly

American and British) bombers and Soviet soldiers.

After the war, Vienna (like Berlin) was divided into sectors under the control of the

various Allied powers (Britain, France, the U.S. and the U.S.S.R.), and for a while

(also like Berlin) the city was a center of cold war intrigue. Repairs to the city

progressed, but many years would be needed to restore it to its former glory. If

you're curious about what the city was like during this time, check out the classic

1949 movie The Third Man, with Joseph Cotton and Orson Welles.

Scene from The Third Man

Unlike what happened in Berlin, the Soviets voluntarily withdrew from Austria in

1955, but only after the other Allied powers signed a treaty promising that Austria

would never join NATO. To date, this promise has been kept, but the country is

thoroughly westernized. It is regularly ranked as one of the most livable cities

in the world, and is a magnet for tourists.

Tourists like us, headed through Vienna's outskirts on our way to its central Old

Town.

Vienna Outskirts

Most of Vienna's attractions to the international tourist community are located

within or just outside a roughly circular road known as the Ringstrasse.

The Ringstrasse follows the path of the former city wall, which was torn

down in the mid-19th Century because it was obsolete as a defense and because it

was an obstacle within a city which had grown well beyond its medieval walls. The

wall had originally been built using a large ransom payment received from England

for the release of Richard the Lionheart, who had been captured in 1192 by

Leopold V, one of the Babenberg dukes, on his way back home from a crusade. The

wall had helped to defend the city from the Turkish siege of 1529 mentioned above,

and again during another Turkish siege in 1683. But by the middle of the 19th

Century, modern weaponry had made city walls pretty useless, and Emperor Franz

Joseph ordered it demolished in 1857. The Ringstrasse actually has

different names in different areas (e.g. Universitätsring near the

university, Opernring near the state Opera House, and Parkring near

the main city park), and during one stretch follows the course of the

Donaukanal. The Donaukanal is a mostly natural branch of the

Danube River which forms the northern boundary of the Old Town.

Old Town and Waterways

Sights in and Around Old Town

We left our train at one of the city's train stations (there are four), called

the Westbahnhof, which is located well outside the Ringstrasse. We'd

considered using the city's Metro system and some walking to get to our hotel (which

was in the Old Town) from the train station, but it was still raining, so we opted

for a taxi instead. But first we stopped in the Westbahnhof to get lunch at

a vendor who had clearly not received training in cultural sensitivity.

Westbahnhof Sign

Food, Escalators and People, Westbahnhof

Politically Incorrect Chinese Food

A taxi got us to our hotel, the Best Western Hotel Das Tigra, but it wasn't easy.

An intersection on the driver's map turned out not to be an intersection after all – one

of the streets crossed over the other one via an overpass, and it was not easy to get

from one street to the other. But the driver eventually solved the puzzle, and we were

able to check in and get a little rest while waiting for the rain to stop.

Hotel Das Tigra

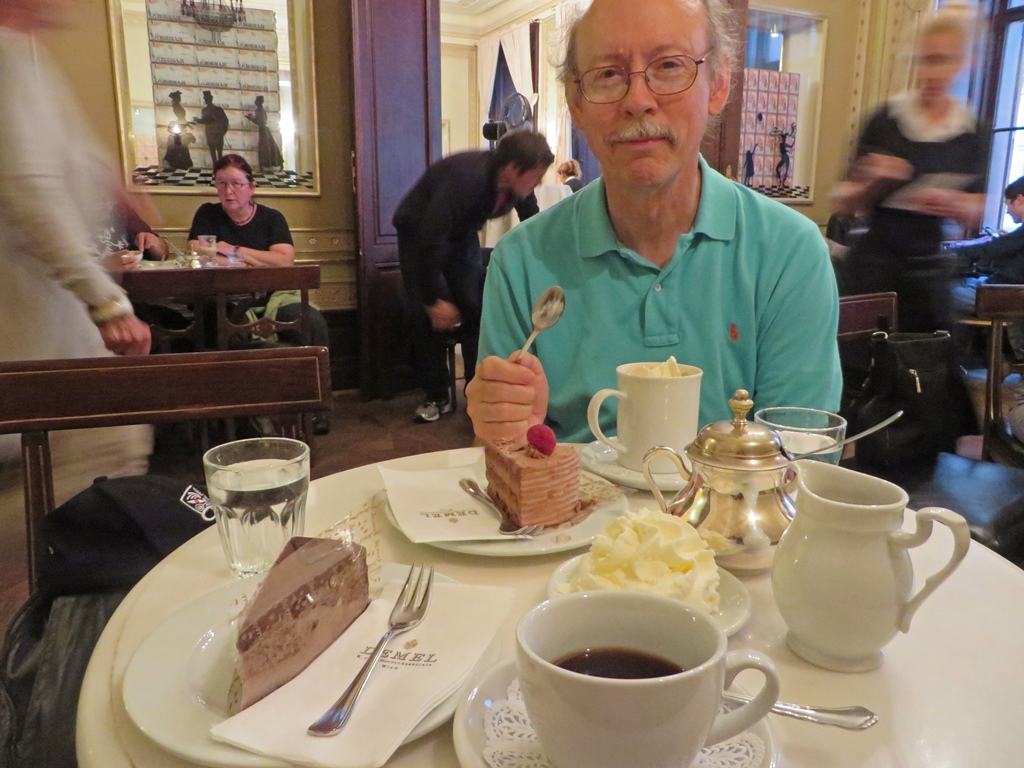

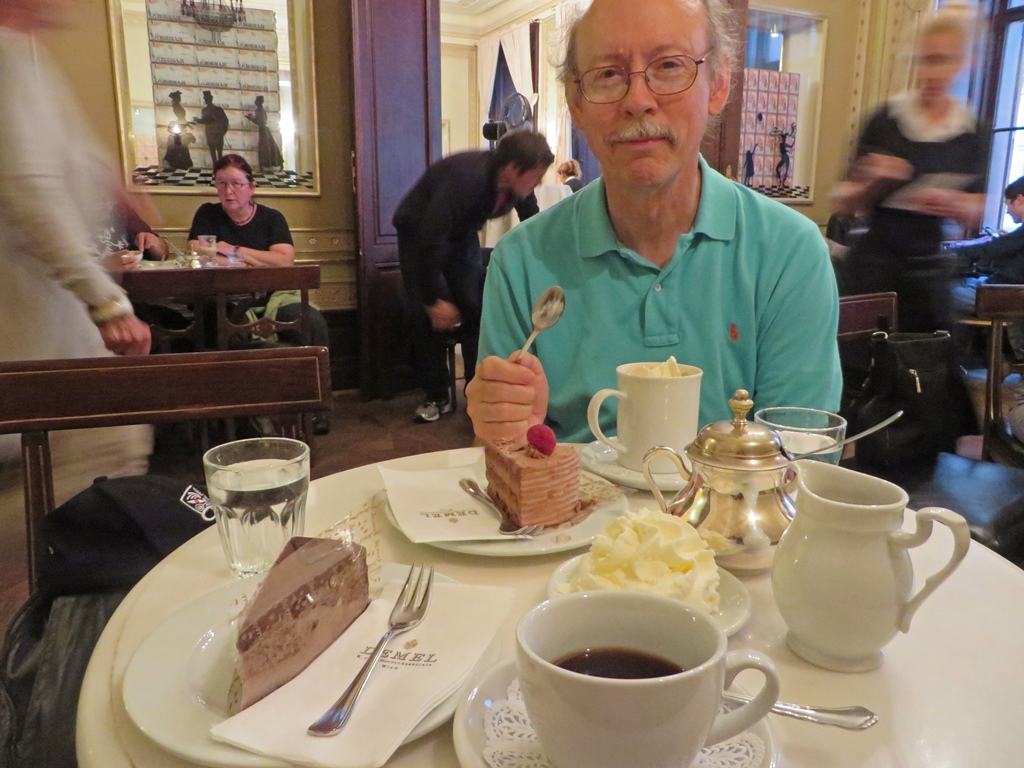

After a while we gave up on waiting for the rain to stop, and we took our

umbrella and went out in search of the

Demel Hofzuckerbäcker/Chocoladenfabrikant,

a famous bakery/chocolatier, where we stopped for a leisurely afternoon snack of

pastries and hot beverages (for which Vienna is justly renowned).

Demel Hofzuckerbäcker/Chocoladenfabrikant

Demel Kitchen

Pastry Case

Bob with Desserts and Hot Drinks

On the way out we noticed stacks of nicely wrapped boxes of chocolates and

small pastries for sale. We didn't buy any though.

Chocolate for Sale

Cones in Window

Boxes for Sale

We started heading back toward the hotel, but took a short detour on the way. As

long as we were in the area, we thought we might take a look at one of the local

churches, the Peterskirche.